Feature

Chinese Umbrellas Inspire Africa’s Heritage Revival

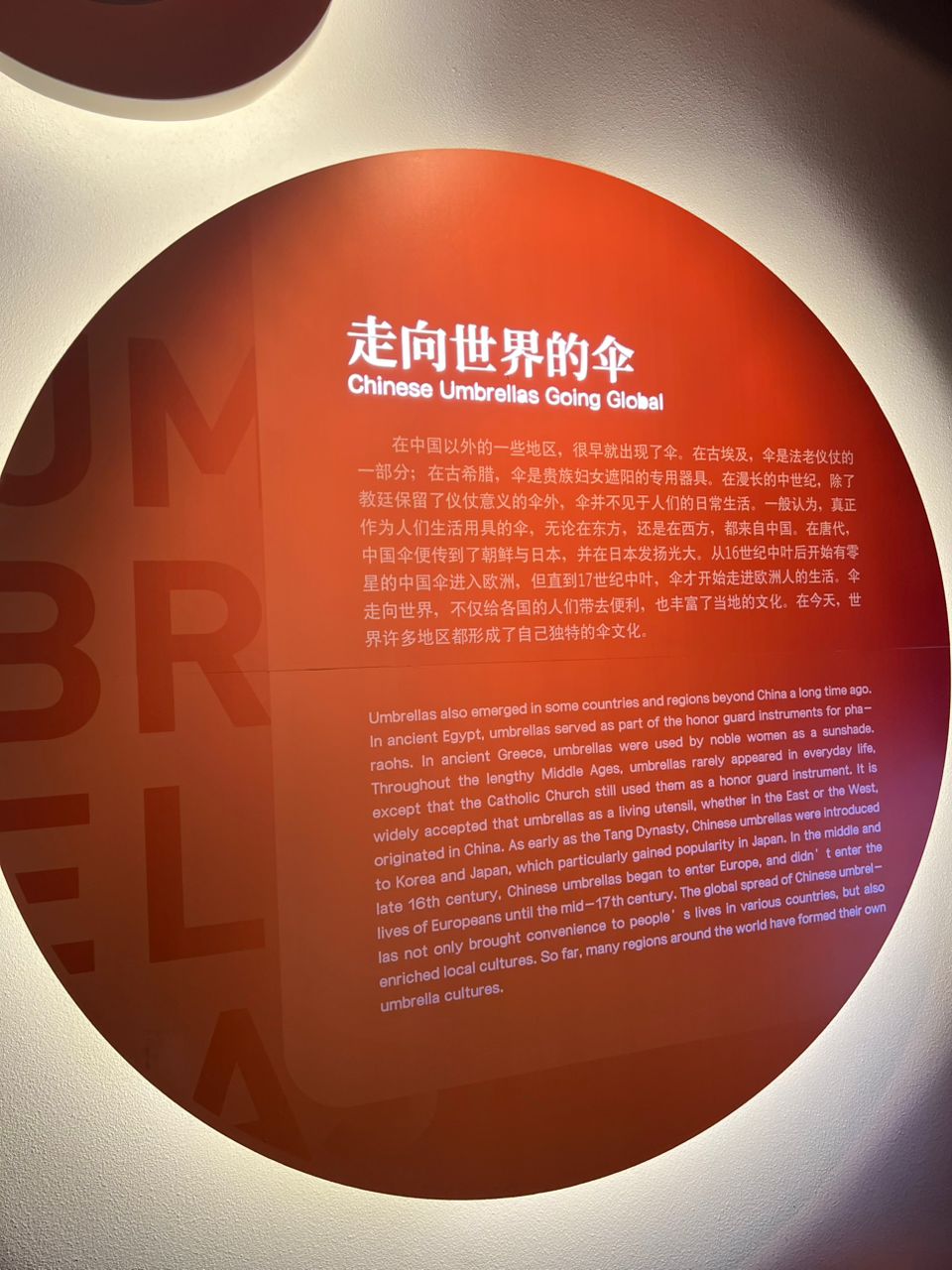

An umbrella is more than a shield from sun or rain, it tells stories. For over two millennia, China’s oil-paper umbrella, or yóuzhǐ sǎn, has symbolised artistry, status, and spiritual harmony. Crafted from bamboo ribs and oiled rice paper, adorned with dragons and peonies, it exemplifies China’s commitment to intangible cultural heritage (ICH).

China’s iconic oil-paper umbrellas go global, blending centuries-old craftsmanship with modern markets. These umbrellas, celebrated for their artistry and cultural symbolism, now inspire international appreciation while showcasing China’s commitment to preserving intangible cultural heritage.

Credit: Hurumende News Hub

Africa, meanwhile, faces its own cultural crossroads. Vibrant Ashanti kyinie umbrellas in Ghana or Zulu ceremonial shades are at risk of fading under the pressures of urbanisation, globalisation, and economic change.

These heirlooms, often undocumented, hold untapped power for identity, economy, and resilience. By examining Chinese preservation strategies rooted in UNESCO frameworks and state support, Africa can reclaim and modernise its own cultural narratives.

The Timeless Canopy: A Historical Tapestry

The Chinese oil-paper umbrella dates to the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE), with legends crediting Lu Ban for its invention around 1046 BCE. Inspired by lotus leaves, early umbrellas used silk stretched over bamboo, later evolving to oiled paper for waterproofing.

The Tang Dynasty, umbrellas became symbols of hierarchy: yellow and red for royalty, blue for nobility. During the Song Dynasty, Fuzhou artisans exported durable versions to Japan and Southeast Asia, blending utility with artistry.

Ming and Qing artisans refined the craft, hand-painting landscapes, phoenixes, and poems, completing over 80 steps per umbrella, from splitting bamboo ribs to glazing paper. Hangzhou emerged as a cradle of the craft, its umbrellas reflecting both elegance and resilience.

Despite industrialisation threatening extinction in the 20th century, revival efforts, like Liu Youquan’s 2006 campaign in Yuhang, restored the art.

Today, UNESCO recognises these umbrellas as ICH, blending heritage with tourism and commerce.

Symbolism Unfurled

Chinese umbrellas carry deep meaning. Round canopies symbolise completeness (yuan), while colours convey blessings: red for joy and fertility, purple for longevity, and white for mourning. In rituals, umbrellas ward off evil, protect initiates, and enhance feng shui.

Artistically, they reflect scholar-artist ideals, with regional variations depicting opera, folklore, and tribal myths. Economically, workshops sustain communities, turning craft into cultural capital.

A Personal Pilgrimage

Visiting Hangzhou’s umbrella trails in 2025 revealed these umbrellas as living poems rather than relics. At the China Umbrella Museum, 2,800 artefacts trace 4,000 years of evolution.

Hands-on workshops allowed me to craft a miniature umbrella, experiencing first-hand the blend of precision, artistry, and resilience passed through generations.

This journey illuminated how cultural trails can animate heritage, offering lessons for Africa’s own traditions.

Preservation Paradigms: China’s Blueprint

China’s post-2003 UNESCO-aligned policies provide legal, financial, and educational support for ICH.

Subsidies revive skills, apprenticeships ensure transmission, and festivals embed traditions in communities.

The result: economic vitality, global recognition, and enduring pride. Adaptive innovations, LED umbrellas, eco-nylon hybrids, demonstrate that heritage can evolve while preserving identity.

Africa’s Shadowed Canopies

Africa’s umbrellas, like Ghana’s kyinie or Zulu ceremonial shades, mirror Chinese symbolism but face sharper erosion.

Colonial plunder and mass-produced imports have undermined handicrafts.

Urbanisation threatens intergenerational transmission: Lagos, Johannesburg, and Nairobi see artisans’ skills fade amid industrial and technological growth.

Intangible heritage, ritual dances, oral narratives, remains underdocumented, leaving traditions vulnerable.

Lessons for Africa

China offers a blueprint: state-backed inventories, youth apprenticeships, and tourism circuits revive interest and sustain craft.

Africa can adapt this model, digitising beadwork, supporting guilds, and developing cultural trails, to protect its legacy while innovating for modern markets.

Sino-African exchanges could blend techniques and motifs, fostering cultural resilience and economic opportunity.

From Tradition to Modernity

The umbrella’s evolution, from imperial luxury to mass-market staple, demonstrates adaptation without loss of identity.

Revivalists fuse old and new: LED-lit or eco-friendly umbrellas extend relevance. For Africa, this signals a path: modernised kyinie or solar-powered parasols can preserve heritage while addressing contemporary needs.

Unfurling Africa’s Future

Heritage is ballast against cultural erosion. By learning from China’s blend of policy, community, and innovation, Africa can revive its umbrellas, beadwork, and textile traditions.

Preserving these symbols ensures sovereignty, creativity, and unity for generations to come.

In a globalised world, our canopies, African, Chinese, shared, can continue to shade and inspire the future.

Feature

Ambassador Ding Zhou Pays Tribute to Fay Chung’s Legacy in Zimbabwean Education

Chinese Ambassador to Zimbabwe, Ding Zhou, recently paid tribute to the remarkable life and enduring legacy of Dr. Fay Chung, a pioneer of Zimbabwe’s education sector and an unwavering champion of social progress.

Reflecting on his personal connection, Ambassador Zhou shared warmly:

“This brings back my fond memories of visiting Dr. Fay Chung as well as hosting her and Chipo Chung at my place. Deeply moved by Dr. Fay Chung’s legendary life story, selfless dedication to Zimbabwe’s education and social progress.”

The Ambassador emphasized that China and Zimbabwe share a common vision—education for all. In his words:

“🇨🇳 & 🇿🇼 share the same vision of championing education for all.”

Moments of reflection and gratitude — Dr. Fay Chung with Ambassador Ding Zhou, celebrating her remarkable legacy. (Pic Credit: Chinese Embassy)

A Legacy Forged in the Liberation Struggle

Dr. Fay Chung’s daughter, Chipo Chung, offered a powerful reflection on her mother’s role during Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle:

“My mum and her friend Comrade Chitofu. During the Liberation Struggle for Zimbabwe, Chitofu ran the education system in the refugee camps while Fay was in charge of Teacher Training. Together they ensured that thousands of young people were educated in Mozambique and continued to learn when they resettled in Zimbabwe after independence through the ZIMFEP (Zimbabwe Foundation for Education with Production) schools. We stand on the shoulders of giants. Aluta continua!”

Through perseverance, vision, and sheer commitment, they laid the foundation for an education system that empowered a generation of young Zimbabweans displaced by war.

Voices of Gratitude from Zimbabweans

Dr. Fay Chung’s impact continues to resonate deeply with those whose lives she touched. Zimbabweans expressed admiration and heartfelt appreciation for her contributions:

- Gody Nkata:

“Dr. Fay Chung’s story is truly awesome and inspiring, thanks for sharing.”

- Levison Chambati:

“She is our former Minister of Education. She has done a lot for this country. We are forever thankful to her contributions during the armed struggle.”

- Forward Chidumba:

“Apart from Mutumbuka, she was one of the best Education Ministers to have ever graced Zimbabwe. She was pro-teachers, she fought for better welfare, and the education system under her was intact and valued.”

- Shadreck Shumba:

“I worked with Dr. Fay Chung in Namibia when she was advisor to Abraham Iyambo. We had dinner several times and she introduced me to comrades there. She used to tell me about you, Chipo, and about Chimurenga stories. The best favor she did for me was introducing me to Ambassador Shin.”

A Giant in Education and Humanity

Dr. Fay Chung’s story is not merely one of professional achievement—it is a testament to courage, sacrifice, and purpose.

From organizing teacher training during the liberation struggle, to shaping Zimbabwe’s post-independence education system, to influencing policy across Africa, her life demonstrates the power of education as a tool of liberation.

Her legacy lives on in:

- The teachers she trained

- The students she empowered

- The leaders she mentored

- The vision she carried — education as a right, not a privilege

Dr. Fay Chung stands as a symbol of commitment to nation-building, cross-cultural friendship, and transformative education.

Her life brought together the spirit of Zimbabwean resilience and a global dedication to human development.

As many have echoed:

“We stand on the shoulders of giants.”

Feature

Under the Same Sky: What China Taught Me About Africa’s Future

By Farai Ian Muvuti

There are journeys that alter one’s geography, and there are those that rearrange one’s mind. My recent travels across China belong firmly to the latter. Long before my flight descended over the ordered expanse of Beijing, I had inherited an image of China shaped by half-truths a monolithic state of stoic people, great walls, and even greater censorship. What I encountered instead was a civilisation alive to paradox: ancient yet futuristic, disciplined yet profoundly human.

Climbing the Great Wall on a crisp October morning, I saw not a relic of defence but a monument to persistence a line of stone that seems to breathe with history. “The man who moves a mountain begins by carrying away small stones,” Confucius once wrote. That patient pragmatism defines China’s ascent. Progress here is incremental, deliberate, and coherent a mosaic built stone by stone rather than a revolution waged overnight.

Later that day, standing atop the wall’s highest rampart, I understood why the myth of China as merely authoritarian misses the essence. What looks like rigidity from afar is, up close, choreography millions of coordinated movements guided by purpose. It is a rhythm born not of fear but of focus.

At BOE’s innovation campus in Beijing, where engineers turn glass into light and pixels into living colour, I saw how that same philosophy animates the digital age. The laboratories were immaculate, yet not soulless: calligraphy hung beside quantum screens; potted bamboo softened the geometry of machines. Engineers spoke of balance, of designing technologies that coexist with the rhythms of human life. Their pride was quiet, grounded in the Confucian belief that the highest skill lies in harmony rather than dominance.

For Africa and Zimbabwe especially this approach offers a revelation. We have been told that progress requires disruption, that only by abandoning our histories can we industrialise. But China’s story suggests another path: that the future can be engineered without erasing memory. Development, I realised, need not mimic the smoke-stack century; it can be re-imagined as a dialogue between innovation and sustainability.

In this spirit, China did not chase the global North’s combustion engines it leapt straight into electric mobility. It did not lament digital disruption it built platforms that re-imagined cinema, education, and commerce. The lesson is clear: to compete with credibility, Africa must locate its own comparative advantages our sunlight, our lithium, our creativity and build around them rather than against them.

The Village That Taught Me About the Future

Travelling south to Zhejiang Province, I discovered Lizucun — once a sleepy hamlet, now a model of rural revitalisation. In the early 2000s it was scarcely electrified; today it welcomes over 650 000 visitors a year. Paved roads thread through fields of tea; cooperative workshops produce crafts once dismissed as quaint; and the entire settlement hums with quiet prosperity.

The “Two Mountains Theory” — that lucid waters and lush mountains are as precious as gold — is not a rhetorical flourish here but a moral compass. Lizucun shows that prosperity and ecology are not competing destinies. The community’s income has risen six-fold, yet its air and streams remain clear. What transformed Lizucun was not money alone but organisation: government enabling, citizens participating, culture commercialised without being commodified.

It reminded me of home. In Zimbabwe’s Eastern Highlands, the same mixture of natural beauty and artisanal skill exists in abundance, but the connective tissue of governance and innovation is often missing. If Lizucun could turn heritage into livelihood, so too could Mutoko or Domboshava. Modernisation, I realised, is not the abandonment of the rural; it is its reinvention.

A few days later, at Ningbo’s Tianyi Ge Museum — the world’s oldest private library — I confronted another kind of transformation. The ancient books have been moved into climate-controlled vaults, a decision that angered purists. Yet a curator told me gently, “We do not worship the dust; we preserve the breath.” Those words stayed with me.

So much of Africa’s heritage remains vulnerable — both materially and conceptually. We guard relics but neglect relevance. China’s model demonstrates that preservation is an act of evolution: a living culture renews itself by translation into modern forms. In Suzhou’s classical gardens, centuries-old stones sit beside Wi-Fi routers, and somehow the harmony persists. The past here is not a museum piece; it is an ecosystem.

That sense of continuity — of negotiating with time rather than resisting it — is China’s most subtle export. It offers Africa a reminder that genuine progress need not sever its roots.

Media, Meaning and the Digital Silk Road

In Beijing, during the Seminar on Regional Online Media for Belt and Road Countries, I witnessed another frontier of transformation: the forging of a digital Silk Road. The sessions, hosted by the China Broadcasting International Economic and Technical Co-operation Company (CBIC), revealed how storytelling itself has become a form of infrastructure.

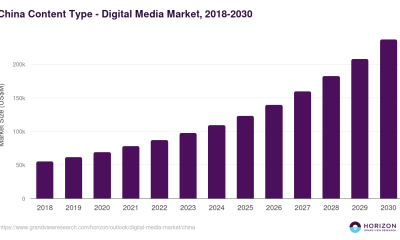

China’s audiovisual industry — now valued at over US $7 billion — operates as a vast ecosystem spanning cinema, streaming, e-commerce, and social interaction. Platforms such as Tencent Video, iQIYI, and Bilibili have redefined what a “film release” means, blending art and algorithm. Artificial intelligence now edits news copy; augmented and mixed-reality studios allow anchors to stand “inside” the story; audiences participate rather than consume.

As one lecturer put it, “Technology will not replace journalists, but journalists who use technology will replace those who do not.”

This approach need not alarm Africa’s media landscape; it should inspire it. Imagine The Southern African Times producing an immersive report on the Kariba Dam or letting readers step virtually into a solar plant in Hwange. With thoughtful curation, immersive media could reconnect citizens to their own realities.

Yet China’s example also carries a warning. The same tools that democratise expression can centralise power. African media innovators must therefore pair ambition with ethics — ensuring that digital storytelling serves enlightenment, not manipulation.

Still, I left the seminar convinced that Africa’s creative future lies in this fusion of art, technology, and public purpose. The question is not whether we can build platforms, but whether we can build trust.

Competing with Credibility — Africa’s Turn to Climb

Pragmatism is China’s quiet superpower. Every major reform — from land policy to high-speed rail aligns state intent with local incentive. Ideology bends before utility. Africa’s leaders could adopt the same temperament: fewer declarations, more delivery.

Indonesia offers an instructive parallel. Facing the twin pressures of decarbonisation and growth, Jakarta has negotiated a US $21.6 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership with foreign partners, including China. Its strategy is not charity but choreography — local content rules, vocational training, and technology-transfer clauses ensure that green investment builds domestic capacity.

Zimbabwe, with its mineral wealth and youthful population, could follow suit. Bilateral projects with China should be structured to guarantee technology transfer and skills development, not merely extraction. Our education reforms must therefore become living frameworks: data-driven, outcome-led, audited annually. We must ask not only how many engineers we graduate, but how many innovators we employ.

Likewise, our energy policy should mirror pragmatism with vision. By unburdening the national grid through decentralised solar systems, we can divert electricity toward manufacturing creating jobs while greening growth. Such a development-comparable energy transition would anchor industrialisation in sustainability rather than sacrifice competitiveness to virtue signalling.

At the core of these reforms lies culture. China’s rise was powered as much by self-belief as by steel and silicon. Its museums, media, and villages are expressions of a civilisation confident enough to modernise without apology. Africa’s own ascent must likewise merge material progress with cultural coherence.

To compete with credibility is not merely to industrialise faster but to believe more deeply in our languages, in our creative industries, in our capacity to define modernity on our own terms. Only then can partnership with China evolve from dependency to dialogue.

When I returned to the Great Wall on my final evening, the wind carried the word suiyuan “to follow fate.” Yet I understood it differently. Fate, in the Chinese sense, is not fatalism but equilibrium: the wisdom of advancing in step with circumstance. Africa’s suiyuan will depend on our ability to harness time rather than chase it.

Rabindranath Tagore, reflecting on his 1924 visit to China, observed that “the world speaks in many tongues, but truth has only one voice that of sincerity.” Beneath the same clouds that once drifted over Li Bai’s inkstone, Africa and China may yet find that sincerity not rivalry as the basis of their shared horizon.

-

Current Affairs1 week ago

Current Affairs1 week agoOperation restore order

-

Crime and Courts2 months ago

Crime and Courts2 months agoMasasi High School Abuse Scandal Sparks Public Outcry

-

Crime and Courts2 months ago

Crime and Courts2 months agoKuwadzana Man Jailed for Reckless Driving and Driving Without a Licence

-

Current Affairs3 months ago

Current Affairs3 months agoMunhumutapa Day: Zimbabwe’s Newest Public Holiday Set for Annual Observance

-

Current Affairs4 months ago

Current Affairs4 months agoBreaking: ZIMSEC June 2025 Exam Results Now Available Online

-

Current Affairs1 month ago

Current Affairs1 month agoBREAKING NEWS: ZANU PF Director General Ezekiel Zabanyana Fired

-

Current Affairs3 months ago

Current Affairs3 months agoGovernment Bans Tinted Car Windows in Nationwide Crime Crackdown

-

Current Affairs2 months ago

Current Affairs2 months agoExposed: Harare GynecologistChirume Accused of Negligence, Extortion, and Abuse